Introduction

If you have been planning for retirement for any period of time, you have likely encountered the 4% Rule. This rule is a commonly utilized rule of thumb for annual retirement withdrawals. It can also be used to determine the amount you need to accumulate to retire safely.

If you have been planning for retirement for any period of time, you have likely encountered the 4% Rule. This rule is a commonly utilized rule of thumb for annual retirement withdrawals. It can also be used to determine the amount you need to accumulate to retire safely.

But exactly how was this 4% calculated and how safe is it to use a withdrawal strategy in retirement? Is accumulating 25 times your estimated retirement annual spending (an inverse of the 4% rule) enough to retire safely? Is is still valid for today’s market conditions?

In this post, we’ll review the origin of the 4% Rule, how it actually works, and it’s pros and cons.

History

It’s the question on the mind of every potential retiree. How much of your nest egg can you withdraw every year without running out of money in retirement? Prior to the 4% Rule, financial advisors often utilized their knowledge of average annual returns on stocks (10.3%) and bonds (5.1%). With these returns, a 60 stock/40 bond portfolio (a commonly recommended allocation) would result in an average return of 8.2%.

These advisors were also aware of the historical average inflation rate of 3.1%. After subtracting the average inflation rate (3.1%) from the average return (8.2%), many advisors recommended that their clients could safely withdraw 5.1% of their portfolios each year.

With a 5% withdrawal rate, would your portfolio survive a sustained market drop (like in 2008)? What would happen during higher periods of inflation (like in 1978 and 2022)? Would the 5% recommendation hold up during a thirty year retirement?

Bring in the 4% Rule

In 1994, William Bengen attempted to answer these important questions. Mr. Bengen published his research in a groundbreaking article entitled “Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data” in October 1994.

The study analyzed historical market data over 50-year periods between 1926. The study looked at various withdrawal rates of theoretical portfolios with allocations ranging from 50% stocks/50% bonds to 75% stocks/25% bonds. The time period reviewed in this study included the Great Depression of 1929, World War 2 (1941-1945) and the recession of 1973.

Bengen then calculated how long these portfolios would have lasted with withdrawal rates of 3%, 4%, 5% and 6%. With a 3% withdrawal rate, all portfolios lasted at least 50 years. With a 4% withdrawal rate, the vast majority (80%) of the portfolios lasted at least 50 years. All of the portfolios lasted at least 33 years. At 5%, more than 25% of the portfolios failed within 25 years.

Most Americans, retiring in their 60’s, should assume a retirement period of 30 years or more. For this reason, most focus on the 4% withdrawal rate described by Bengen. Those following the FIRE (Financial Independent Retire Early) movement, with a potential 50-year retirement, would be wise to assume a 3% or 3.5% initial withdrawal rate.

“Assuming a minimum requirement of 30 years of portfolio longevity, a first-year withdrawal of 4 percent, followed by inflation-adjusted withdrawals in subsequent years, should be safe.”

-William Bengen, “Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data”; Journal of Financial Planning

Supporting Data

In 1998, a study commonly referred to as the Trinity Study directly built on, supported, and popularized Bengen’s findings fixing the “4% Rule” in the lexicon of potential retirees. The 4% rule became the gold standard to which other withdrawal strategies were compared. In 2006, Bengen himself updated his previous findings utilizing small-cap stocks resulting in a 4.5% withdrawal rate. We’ll discuss many of these other withdrawal strategies in future posts.

Mechanics of the 4% Rule

It is vital to have a detailed understanding of how the 4% Rule works. Bengen’s study included only portfolios with 50% to 75% stocks and 25% to 50% bonds. Retirees should be reluctant to apply the 4% Rule to portfolios outside of these limits particularly with less than a 50% stock allocation. Many potential retirees think that this rule allows them to withdraw 4% of their portfolio year after year regardless of their portfolio’s performance. This is inaccurate. Withdrawing 4% of your current portfolio year after year could be disastrous during long periods of declining markets.

It is vital to have a detailed understanding of how the 4% Rule works. Bengen’s study included only portfolios with 50% to 75% stocks and 25% to 50% bonds. Retirees should be reluctant to apply the 4% Rule to portfolios outside of these limits particularly with less than a 50% stock allocation. Many potential retirees think that this rule allows them to withdraw 4% of their portfolio year after year regardless of their portfolio’s performance. This is inaccurate. Withdrawing 4% of your current portfolio year after year could be disastrous during long periods of declining markets.

In Bengen’s model, the retiree withdraws 4% of his/her portfolio for the first year. From that point forward, future withdrawals are based on the previous years withdrawal in addition to that years inflation rate. Let’s work through an example. When a retiree first retires with a $1,000,000 portfolio, he/she could safely withdraw 4% or $40,000 for their annual expenses. If that years inflation rate was 3%, the retiree would withdraw $41,200 (or $40,000 plus 3%) in the second year of their retirement. In the third year, the withdrawal amount would be $42,436 (or $41,200 plus 3%) and so on. According to Bengen, this withdrawal pattern could continue year after year regardless of the markets performance (based on historical returns).

The good news here is that there is an annual increase in each year’s withdrawal, compensating for inflation and maintaining your annual buying power.

Utilization of the 4% Rule

Millions initially utilized the information in this study not as a withdrawal strategy, but as a way to determine how much to save prior to retirement. This is done by dividing their estimated annual expenses by 4% (or 0.04). Let’s work through an example. What size portfolio would support a $100,000 initial withdrawal in retirement? The answer is $2,500,000 or $100,000 divided by 0.04. (It’s actually easier to simply multiple the initial annual withdrawal by 25 (the inverse of dividing by 0.04) ($100,000 x 25 = $2,500,000).

Once these individuals retire, it’s time to decide if the 4% Rule can also be used as their retirement withdrawal strategy.

The 4% Rule as a Withdrawal Strategy

So, is this simple, straightforward strategy good enough to utilize as your withdrawal strategy? The 4% Rule may not have been the first data-driven withdrawal strategy. However, it was the first widely accepted and most rigorously back-tested strategy. Bengen’s method depended on historical simulation (rather than “average annual returns”) and incorporated inflation into his calculations. His work popularized the whole “safe withdrawal rate” (SWR) concept utilizing back testing.

A such, the 4% Rule became the gold standard to which other withdrawal strategies (Guyton-Klinger method, Vanguard Dynamic Spending, 95% Rule, Endowment Strategy, etc.) are compared. However, the question remains. Is the 4% Rule, which is more than thirty years old, still a reasonable withdrawal strategy?

To answer that, question, let’s look at some pros and cons.

Pros of the 4% Rule

Since its creation, the pros and cons of the 4% Rule have been hotly debated. The pros of the withdrawal strategy include:

- Simplicity: The 4% Rule is easy to use. Once retired, withdraw 4% of your portfolio’s value. The following year, the withdrawal amount is increased by the previous year’s rate of inflation. Lather, rinse and repeat. The advantage of this methodology is that the retiree’s buying power is preserved year after year. The math and decision-making process could not be easier. No adjustments are necessary based on your portfolio performance, up or down.

- Historical Success: The withdrawal rate of 4% was chosen for its 100% historical success rate over all 35-year retirement periods beginning in 1926 including some that included some of the countries worst financial periods.

- Inflation Adjusted: The 4% Rule includes annual inflation adjustments maintaining the retiree’s buying power for the duration of the retirement. However, these annual adjustments may actually overcompensate for actual spending since annual retirement spending trends to actually decrease 1% to 2% annually for the first fifteen years of retirement. This fact may make the 4% Rule too conservative.

Cons of the 4% Rule

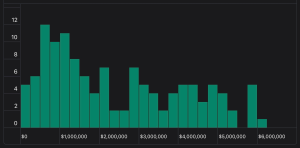

- Independent of Market Conditions: Annual withdrawals are not adjusted based on market fluctuations. Proponents consider this to be strength contributing to the simplicity of method. Critics point out that no increases in buying power occur even if the portfolio value dramatically increases. This may result is leaving a significant amount of “money on the table,” unutilized by the retiree. Modern analysis of the 4% Rule reveals that a retiree who retires with $1,000,000 has 50% chance of having least $2,000,000 and a 30% chance of having at least $3,000,000 in their portfolios after a 30 year retirement. Other withdrawal strategies, such as the Guyton-Klinger Method, allow for a higher initial withdrawal rate (as high a 5.6%) as long as the retiree is willing to occasionally forego inflation adjustments and rarely decrease their annual withdrawals.

- Limited to a 35-year retirement: The method assumes a retirement of no more than 33 years. The 4% withdrawal rate may not be appropriate for those retiring early with a retirement period greater than 33 years.

- “Historical returns may not be indicative of future performance”; Every investor is familiar with this common disclaimer. Bengen’s study include three periods of significant financial turmoil: the Great Depression (1929), World War 2 (early 1940’s) and the Great Recession (early 1970’s). However, there may be a situation in the future that does not support a 4% withdrawal rate over a 33 year period of time.

- Taxes: The 4% Rule does not take taxes into account. The retiree will need to pay any taxes incurred from the annual withdrawal. This is true for any withdrawal strategy.

Fees: Retirees with portfolios actively managed by an advisor (under an assets under management (AUM) agreement) are often charged 1% or more of their portfolio value on an annual basis. These exorbitant fees immediately reduce the “4% Rule” to the “3% rule,” decreasing the available annual funds by 25%! This is actually not a problem with the 4% Rule (or any other withdrawal strategy). Its a problem with the financial industry in general. Avoid “assets under management (AUM)” arrangements at all cost. (More on this important point in a future post.)

Fees: Retirees with portfolios actively managed by an advisor (under an assets under management (AUM) agreement) are often charged 1% or more of their portfolio value on an annual basis. These exorbitant fees immediately reduce the “4% Rule” to the “3% rule,” decreasing the available annual funds by 25%! This is actually not a problem with the 4% Rule (or any other withdrawal strategy). Its a problem with the financial industry in general. Avoid “assets under management (AUM)” arrangements at all cost. (More on this important point in a future post.)- Better Options?: Other strategies, such as the Guyton-Klinger method, have demonstrated significantly higher initial withdrawal rates, such a 5.6%. (More on this option in a future post.)

The 4% Rule is Pessimistic

It is also important to remember that the 4% Rule is a ‘worst case scenario.” Four percent is the lowest withdrawal rate that will likely allow for a thirty-five year retirement without running out of money. As noted earlier, almost 75% of the portfolios, after thirty years of utilizing the 4% Rule, increase in value over the duration of retirement with the average portfolio increasing to 140% of its original value. Two thirds of retirees will end there retirement with portfolios that are greater then when they started. Two thirds! Let that sink in.

Some look at this fact as an advantage of the method. This withdrawal method usually leaves a large portfolio as legacy to your heirs. Others, particularly those without heirs, point out that a lot of money is usually left on the table.

Since Bengen’s study, a number of withdrawal strategies have been developed attempting to improve upon the strategy and overcome the potential shortcomings of the 4% Rule. Dynamic withdrawal strategies, for instance, offer flexibility by adjusting spending in response to changes in market performance or portfolio value.

Some of these dynamic withdrawal strategies have the advantage of supporting a higher withdrawal rate, at least initially. Such approaches aim to maximize income while preserving the longevity of the retirement portfolio. The downsides to many of these approaches include their perceived complexity and the potential need to periodically decrease annual withdrawals.

Moreover, some retirees opt for a hybrid approach, combining the principles of the 4% rule with other strategies to mitigate risks and enhance flexibility. Many retirees that attempt to navigate the complexities of these dynamic withdrawal strategies often return to the 4% Rule because of its simplicity and success rate.

Conclusion

The 4% rule remains a valuable tool in retirement planning (in calculating the size of the portfolio in order to retire safely), offering a structured, simple framework for determining withdrawal rates (4% initially and annual inflation adjustments) and managing portfolio sustainability. However, it is not without its criticisms and limitations, necessitating a nuanced understanding and consideration of alternative strategies.

The bottom line is that the 4% Rule has worked well when back tested and will likely continue to work well for the vast majority of retirees. It can initially be used as a rule of thumb to calculate the size of the nest egg necessary to retire. It can then be used as a simple, reliable withdrawal strategy for the vast majority of retirees balancing a reasonable withdrawal rate with maintenance of buying power for the duration of your retirement and, for most, leaving a legacy for your heirs.

Author’s Conclusion

The 4% Rule will likely serve most retirees well. In fact, its the withdrawal strategy that I use. Why? It’s simple, tested and reliable. My “concern” with the strategy, as noted above, is that most retirees end up with a portfolio worth 2, 3 or even 6 times its initial value. While this is a nice problem to have, it does suggest that I can spend more than the initial 4% with inflation adjustments. Of course, this can only be determined retrospectively.

My solution? I have two solutions for this “problem.” The first is simple. Enjoy the 4% Rule as designed and leave the inflated portfolio to my children and future grandchildren. I could leave it to posterity posthumously or gift it to my kids and grandkids while still living. Perhaps I’ll fund my grandchildren’s U-529 funds with the inflated portfolio.

My solution? I have two solutions for this “problem.” The first is simple. Enjoy the 4% Rule as designed and leave the inflated portfolio to my children and future grandchildren. I could leave it to posterity posthumously or gift it to my kids and grandkids while still living. Perhaps I’ll fund my grandchildren’s U-529 funds with the inflated portfolio.

The second (and perhaps more self-centered and controversial) solution is to consider “re-retiring.” If my theoretical $1,000,000 grows to $2,000,000 five years after retirement, I could decide to “re-retire.” At this point, I could increase my annual withdrawal up to $80,000 (or 4% of $2,000,000). However, by “re-retiring” and increasing my annual withdrawal amount dramatically, I significantly increase my “sequence of returns risk.”

But what if this “re-retirement” was followed by a market downturn? In this case, I could quickly pivot to my original withdrawal amount (since I lived on that amount in the past). The suggestion of “re-retirement” will be criticized by many financial advisors (and maybe rightfully so). The risk of portfolio depletion in my remaining retirement increases. These risks were close to 0% prior to “re-retirement” because of the significant increase in the value of the portfolio.

Leave your thoughts on “re-retirement” in the comments.